Each day between now and the conclave to elect a successor to Pope Francis, on a date yet to be set, John Allen is offering a profile of a different papabile, the Italian term for a man who could be pope. There’s no scientific way to identity these contenders; it’s mostly a matter of weighing reputations, positions held and influence wielded over the years. There’s also certainly no guarantee one of these candidates will emerge wearing white; as an old bit of Roman wisdom has it, “He who enters a conclave as a pope exits as a cardinal.” These are, however, the leading names drawing buzz in Rome right now, at least ensuring they will get a look. Knowing who these men are also suggests issues and qualities other cardinals see as desirable heading into the election.

ROME – It’s a matter of historical record that years before the conclave of 2005 that elected Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger as Pope Benedict XVI, a group of center-left European prelates, which came to be known as the “Sankt Gallen Group” for the Swiss city where they met, consciously strove to find a less doctrinaire alternative for the next pope and felt they had their man in Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina.

Bergoglio didn’t prevail in 2005, but he went on the papacy eight years later in the conclave of 2013.

So far as we know, there isn’t any analogous Sankt Gallen Group today on the Catholic center-right scheming to ensure the election of a more conservative figure this time around. As a thought exercise, however, let’s assume there was such a cabal: Who might their man be?

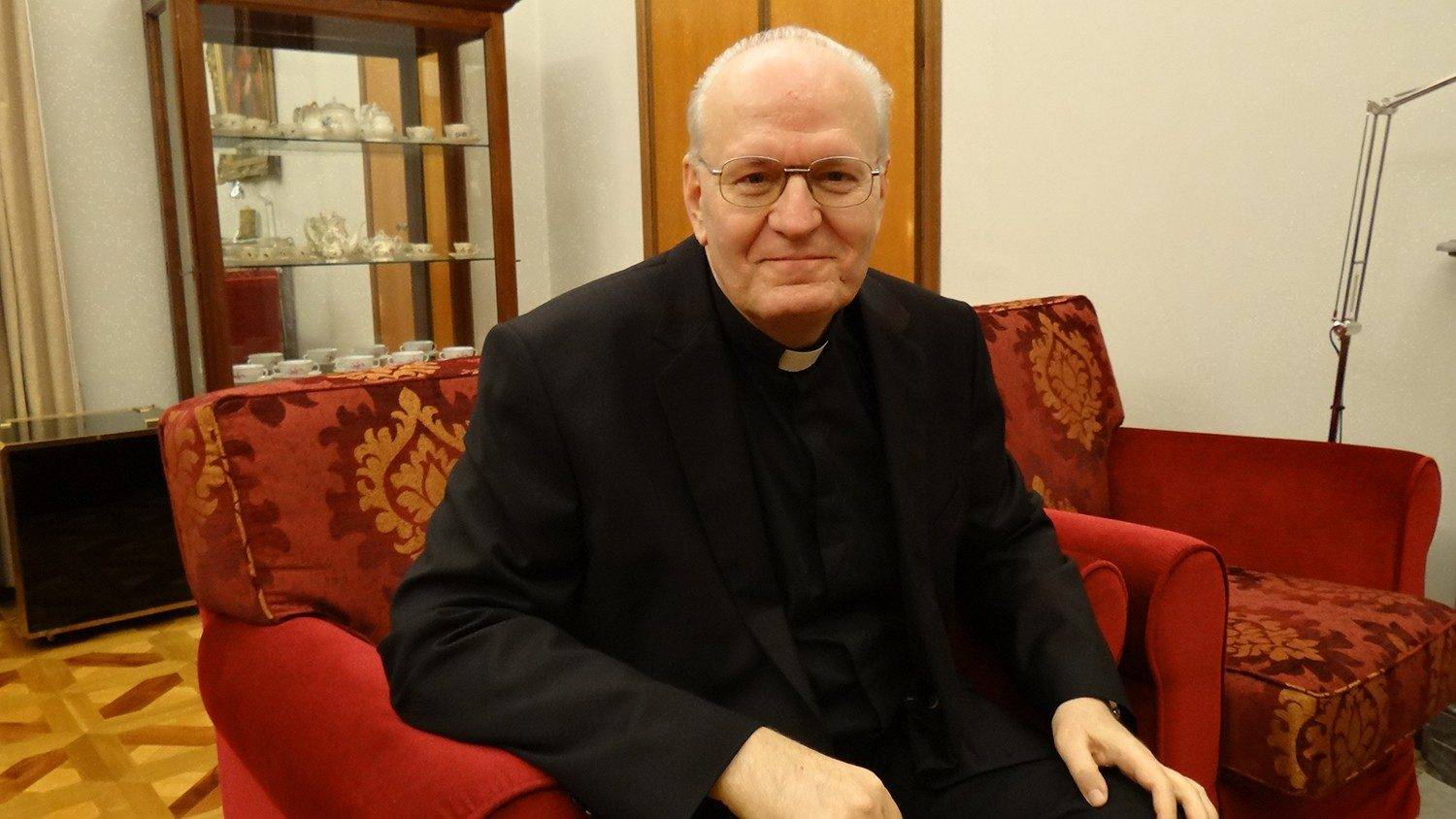

For a while now, the consensus answer to that question has been 72-year-old Cardinal Péter Erdő of Budapest in Hungary, making him the most obvious, and perhaps the most promising, “discontinuity” candidate in the looming conclave.

Born in 1952 as the first of six children, Erdő grew up in a committed Catholic family in which he would later say that “the faith was woven into the fabric of our lives.” In that matrix it was natural for him to feel the stirrings of a vocation to the priesthood. He entered the seminary in both Esztergom and Budapest and was ordained in 1975. It turned out the young Erdő had a nimble mind, so he was sent for further studies to the Pontifical Lateran University in Rome, where he discovered an aptitude for canon law.

For some time it seemed Erdő was destined for an academic career, serving as a professor of theology and canon law at the seminary in Esztergom and as a guest lecturer in a string of European universities. In November 1999, however, he became an auxiliary bishop in Székesfehérvár, and it seemed clear to everyone his rise up the ecclesiastical ladder wasn’t destined to stop there.

In December 2002 Erdő was named the Archbishop of Esztergom-Budapest, making him the “Primate of Hungary,” and when Pope John Paul II made him a cardinal in 2003 at the tender age of 51, Erdő was widely seen as among new stars in the Catholic firmament.

Little that’s happened in the years since have disabused anyone of that notion. Erdő was twice elected president of the European bishops’ conference, in 2005 and 2011, suggesting he enjoys the respect and trust of his fellow prelates. He also clearly is taken seriously in Rome; among other things, he was given the über-sensitive assignment in 2011 of mediating a dispute in Peru between the strongly conservative Cardinal Juan Luis Cipriani Thorne and the more left-leaning Pontifical Catholic University.

In 2014 and 2015, Erdő served as the relator, more or less the chairman, of Pope Francis’s deeply contested two Synods of Bishops on the family, where the burning question pivoted on whether divorced and civilly remarried Catholics should be able to receive communion. Though it seemed clear the pontiff wanted an affirmative answer, Erdő didn’t back off his own more restrictive view, using his opening address in 2015 to insist that the ban on communion in such circumstances isn’t an “arbitrary prohibition” but “intrinsic” to the nature of marriage as a permanent union.

On other fronts too, Erdő profiles as generally cautious and conservative.

When Pope Francis called upon parishes and other Catholic institutions to take in migrants and refugees at the peak of the European migrant crisis in 2015, for instance, Erdő seemed to throw cold water on the idea, warning that indiscriminately harboring refugees could make the church complicit in human trafficking.

Erdő enjoys generally warm relations with the Fidesz government in Hungary under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. In September 2023, he accepted an invitation to attend an exclusive annual picnic for Fidesz insiders and VIPS, creating the impression in some quarters of a cozy tie between church and state. Some even believe that state-controlled media in Hungary are consciously trying to promote the candidacy of their native son for the Throne of Peter.

Arguably, Erdő’s rapport with Orbán might give him a leg up on some of the challenges of statecraft he’d face as pope.

Erdő recently was among several cardinals denounced by the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests for alleged cover-ups of clerical sex abuse in a case involving a victim sued by diocesan officials, though supporters of the Hungarian prelate insist his role in the matter was marginal and entirely appropriate.

What’s the case for Erdő?

Fundamentally, he comes off as the ideal candidate for those wanting the steer the church in a more conventional direction, but without directly repudiating the legacy of Pope Francis. Erdő is careful, diplomatic, and not someone to court public conflict; one Italian newspaper has dubbed him the “friendly traditionalist.”

Erdő’s background in church law would help him sort through the legal thicket created by the torrent of new legislation unleashed in the Francis years as part of his effort to promote Vatican reform. His wide experience of European affairs would also be an asset at a time when the Atlantic alliance seems to be unraveling and Europe is redefining its global role, from the push for a common defense to trade policy, creating an opening for the papacy to play a key moral and spiritual role.

Further, no one questions that Erdő has the gravitas, meaning the intellectual and cultural depth, to be pope. On his watch, most observers feel, the church would be in safe hands.

The case against?

No matter how friendly and diplomatic Erdő may be, his election would nonetheless inevitably be taken as a negative verdict on the Francis papacy, and that may be a step that many of the 135 cardinal electors just aren’t prepared to take.

Moreover, some say that while Erdő may pack gravitas, he lacks charisma, so his papacy would be a period in which the church lacked a compelling personality at the top of the system who can force the world to pay attention to its message.

There’s also concern in some quarters that after the global outreach of the Francis papacy, and at a time when almost three-quarters of the world’s 1.3 billion Catholics live outside the West, the election of such a Western and European figure might represent a step back rather than forward.

Twice during the Francis years, Erdő had the privilege of helping to organize papal trips to Hungary, in 2021 and 2023. It remains to be seen if he’ll be part of yet another papal outing to his home country – this time, with Erdő himself as the VIP visitor in white.