Senior Catholic Church leaders are already discussing what the late Pope Francis’s successor will need to tackle first and foremost after his election, whenever it comes.

On the agenda for the cardinals choosing a successor to Francis will be the scandal of sexual abuse and the crisis of coverup that has been plaguing the Church for decades.

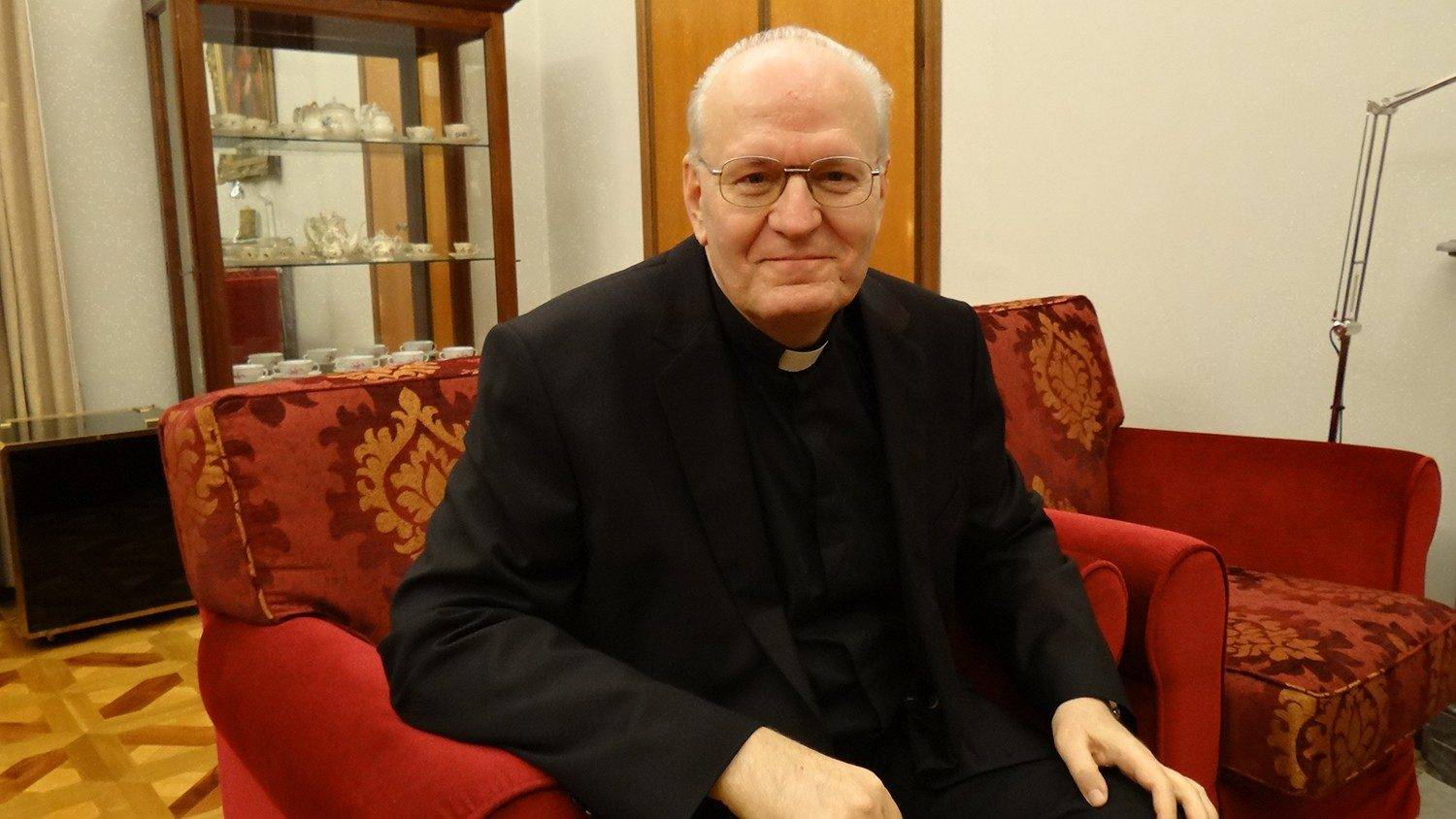

That is one reason why the news that Cardinal Roger Mahony, the retired archbishop of Los Angeles, would be taking part in the sealing of the Pope Francis’s coffin on Friday, was received with surprise and shock.

The 89-year-old Mahony played a central role in the abuse scandal and was accused in 2013 of shielding priests from prosecution by having them moved to other dioceses when facing abuse allegations.

Mahony apologized “for my own failure to protect fully the children and youth entrusted into my care,” calling the abuse “a terrible sin and crime.”

That same year, he was barred from certain activities by his successor, Archbishop José Gomez. Soon after, however, the Church in LA issued a statement saying Mahony was still “in good standing” in the archdiocese.

None of that came up in the statement issued by the archdiocese after Mahony’s role in Francis’s burial was announced.

Mahony is the most senior “cardinal priest”, which is why he is one of the nine cardinals taking part in the burial. (The College of Cardinals is divided into “cardinal bishops”, “cardinal priests”, and “cardinal deacons”.)

In a statement to CNN on Thursday, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles described Mahony’s official role in the ceremonies as a blessing.

“Cardinal Mahony is our Archbishop Emeritus. He retired in 2011 as Archbishop of Angeles and has continued his ministry in our Archdiocese as a retired archbishop,” the archdiocese said. “He has always been in good standing.”

It continued, “We are blessed to have Cardinal Mahony represent our Archdiocese in Rome for the funeral of our Holy Father and the election of our new Pope.”

The Los Angeles cardinal himself noted his pleasure in playing such a significant role in the papal funeral.

“I was stunned and felt honored when I received the news to have been chosen for these special roles,” said Mahony. “Pope Francis and I had a special friendship over the years, and we exchanged personal letters often.”

“God’s surprises never seem to end, and I am joyful that someone from the Archdiocese of Los Angeles was chosen for this role,” the cardinal said.

“It is yet another example of the importance of our wonderful Archdiocese. I carry out these roles with gratitude to the extraordinary Catholic community of Los Angeles under the leadership of Archbishop José Gomez, our Auxiliary Bishops, our priests and deacons, our men and women of Consecrated Life, and our outstanding lay Catholics. May our Risen Lord continue to bestow blessings upon all of us,” Mahony added.

Mahony’s role in the funeral activities didn’t “bestow blessings” in the view of groups set up to defend victims of abuse in the Church.

“Shame on him for participating in the public rites for Pope Francis, and shame on the College of Cardinals for allowing him to do so,” said Anne Barrett Doyle of the group Bishop Accountability, in a message to Reuters.

David Clohessy, a former director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, told Reuters the role “sends the signal to complicit bishops that… they will still be protected and honored by their peers.”

Vatican officials surely didn’t appreciate Mahony mentioning a “special relationship” with Pope Francis, and his claim the two men “exchanged personal letters often.”

The bruhaha over Mahony is coming as Peruvian Cardinal Juan Luis Cipriani arrives for the funeral. Although over 80 – so ineligible for the conclave – it was revealed in January that he was sanctioned by the Vatican in 2019 after allegations were made that he committed an act of sexual abuse in 1983. Cipriani has strongly denied the accusations saying he has never abused anyone at any time.

Still, both cases bring attention to the decidedly mixed record Francis has had on tackling abuse.

The pope had the strongest laws passed to combat clerical abuse during his rule, including setting up the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors early on in his reign and instituting Vos estis lux mundi in 2019, which establishes “universal procedures aimed at preventing and combating these crimes that betray the trust of the faithful.”

However, Francis on a personal level often favored the protests of accused clergy – who, after all, have more face-to-face meetings with the pope – over the accusations of their victims.

In Chile in 2018, the pope strongly resisted accusations against Bishop Juan Barros, who was said to have witnessed abuse committed by Father Fernando Karadima – a powerful and popular Chilean celebrity priest – who was later punished for serial sexual abuse. (Francis later apologized for this.)

Bishop Gustavo Óscar Zanchetta of Argentina was one of the first men raised to the episcopate by Francis after his election in 2013. In the summer of 2017, he stepped aside citing “a health problem.” Later that year, he was appointed assessor of the Administration of the Patrimony of the Apostolic See (APSA), the Vatican’s “central bank.”

It turns out, however, allegations of sexual impropriety had been made against Zanchetta several times, beginning some two years before his resignation ostensibly for reasons of ill health, and several years before formal accusations reached the Vatican no later than early January 2019.

Francis said he believed Zanchetta when he denied the accusations and said one ought to favor the accused when in doubt.

The most notorious example is that of now deceased ex-priest and ex-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, who was accused of several sexual crimes, and given several tasks by the pope despite the claims against him.

Francis’s passing also left unfinished business.

When pope Francis died, the case against the disgraced former celebrity Jesuit mosaic artist, Father Marko Rupnik, was still awaiting trial. Rupnik is accused of abusing dozens of victims, most of them women religious. Only after massive international outcry and a direct rebuke from the pope’s own point man on safe environments, Cardinal Sean O’Malley, did Francis agree to reopen the case against Rupnik after it had been closed on a technicality despite mountains of evidence.

That was nearly a year and a half ago.

At an April 24 press conference in Rome, Jesuit Superior General Arturo Sosa said Francis “always acknowledged his limitations, his mistakes, and his slowness.”

“With regard to abuse cases, I think the Church is not in the same place when Pope Francis was elected. That’s without a doubt. It hasn’t been a straight line… but the Church has advanced in that direction,” he said.

Even if the Church has moved forward, the abuse crisis is still one of the main issues facing the Church as it awaits the next pope in the coming days.

Follow Charles Collins on X: @CharlesinRome