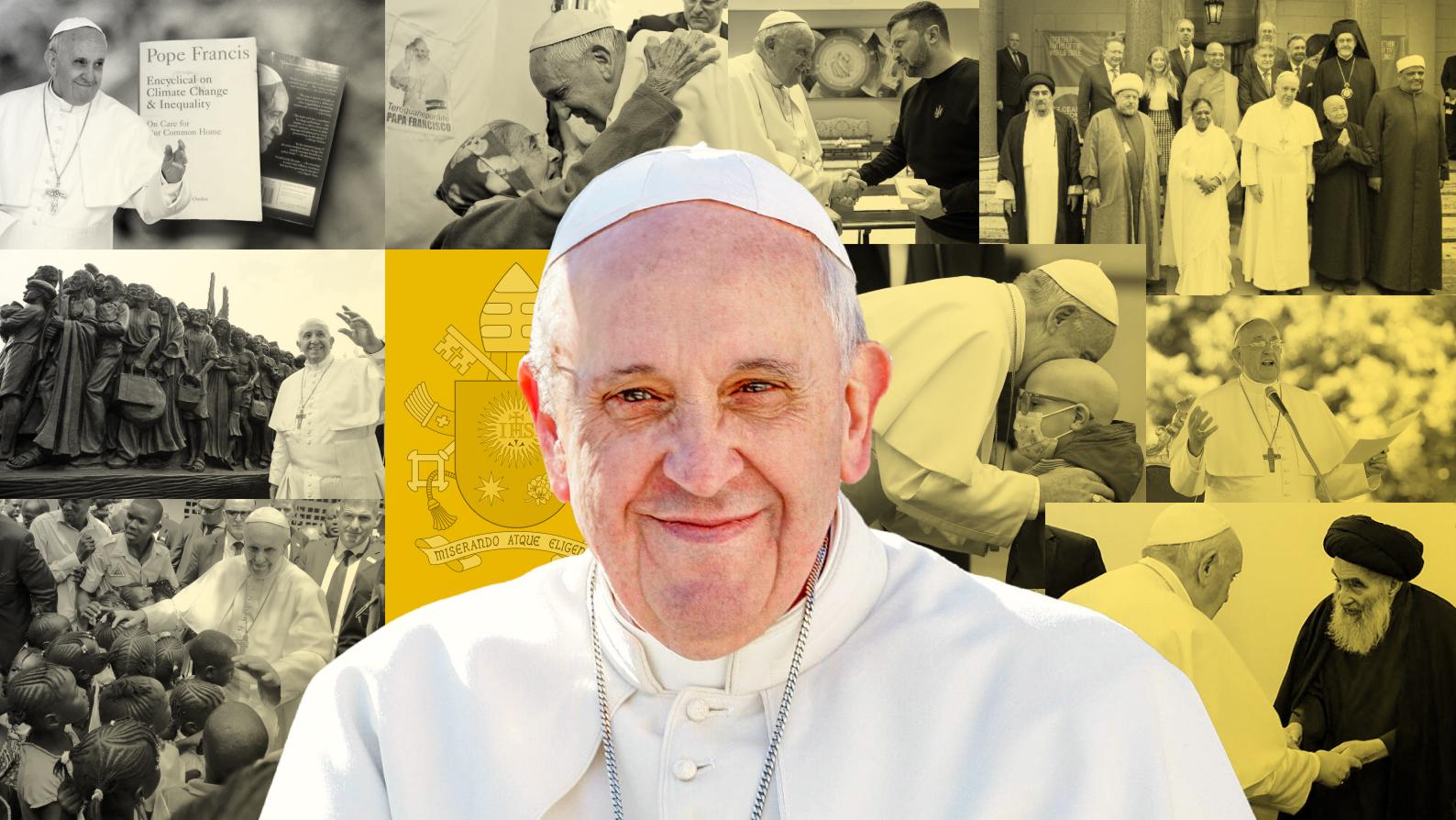

ROME – When Pope Francis was elected to the Throne of Peter on March 13, 2013, he was largely unknown to the wider world. Even many of his fellow Argentines felt they had only a vague, indistinct impression of a man who, in their experience, had tended to shun the spotlight.

Within days, however, the new pontiff had established a narrative about himself which utterly electrified public opinion, and which would endure to the very end: A humble, simple man of the people, “the world’s parish priest,” who spurned luxury and privilege in favor of proximity to the underdogs and the excluded.

This was the pontiff, after all, who took the name “Francis” in homage to Catholicism’s most iconic and beloved saint, the “little poor man” of Assisi; the pope who rejected the marble and gold of the Papal Apartments in favor of the Domus Santa Marta, a modest hotel on Vatican grounds; the pope who returned to the clerical residence where he’d stayed prior to his election to pack his own bag and to pay his own bill; and the pope who, 15 days later, spent his first Holy Thursday not in the ornate setting of St. Peter’s Basilica, but at a youth prison in Rome where he washed the feet of 12 inmates, including two Muslims and two women.

So compelling was the personal story of the new pope that it was easy to ignore the structural and historical forces beneath his maverick style. The most significant transition in Catholicism in the 20th century was a demographic shift from the global north to south in terms of the faith’s center of gravity, and as history’s first pope from the developing world, Francis put a face and an agenda on that epochal change.

If Francis was often jarring to first-world sensibilities, that may have been no more than a long-overdue adjustment to the new realities of Catholicism in the 21st century, when more than two-thirds of the global Catholic population of 1.4 billion lives outside the West, with very different attitudes, instincts and priorities.

However one explains it, the fact is that Pope Francis generated affection and blowback in almost equal measure across 12 fraught and tumultuous years.

Only those ideologically driven to do so would call the Francis papacy a “trainwreck.” Yet even many of his most ardent admirers would at least concede it’s been a roller coaster, full of dizzying highs and bone-crushing lows. For those will elect his successor, that may be a prescription for some of the substance of the Francis era but in a somewhat smoother ride, without the constant chills, thrills and spills.

With his death April 21, the day after Easter, history will now begin to sort out the layers of the Francis revolution in Catholicism, trying to make sense of one of the most remarkable figures in the long history of the papacy. American Cardinal Kevin Farrell, the custodian of the Holy See during a transition between papacies, was the one to make the announcement Monday morning.

Farrell said the news was conveyed to the College of Cardinals “with deep sorrow” and that Francis’s entire life “was dedicated to the service of the Lord, and his Church.”

“He taught us to live the values of the Gospel with fidelity, courage and universal love, in a particular way favoring the poorest and marginalized,” he said. “With immense gratitude for his example as a true disciple of the Lord Jesus, we entrust the soul of Pope Francis to the infinite merciful love of the one and triune God.”

The ironies of his reign were thick. Francis was a pope who extolled human fraternity as the cornerstone of his social agenda, yet who at times struggled to create a fraternal climate within the Church he led. He was a pope who preached synodality and decentralization, yet who often seemed to rule by decree, issuing more motu proprio, meaning amendments to Church law under his own initiative, than any other pope in history.

Pope Francis was a “great reformer” whose reforms occasionally seemed uneven, long on promise but short on execution – including on the two greats sources of scandal he inherited, clerical sexual abuse and Vatican finances. Francis was also a multilateral pope, history’s first pontiff from the developing world, yet his theological outlook sometimes appeared to owe more to 20th century Europeans than to 21st century Africans or Asians.

At his best, Francis led a great “pastoral conversion,” emerging as the “Pope of mercy” who reminded the Church that the sabbath is made for man, not man for the sabbath. In service to that spirit, he often seemed to positively radiate a spirit of Christian love.

In November 2013, for example, during a routine Wednesday General Audience, Francis caught sight of Vinicio Riva, a 53-year-old Italian man suffering from a severe case of neurofibromatosis which leaves his body covered from head to toe with growths, swelling and sores. Unlike most people, who cross streets to avoid coming into contact with Riva, Francis made a beeline and wrapped him in a tight embrace that seemed to go on much longer than a simple photo op would have required.

“He didn’t have any fear of my illness,” Riva said afterwards. “He embraced me without speaking … I quivered. I felt a great warmth.”

Such moments were core features of the papacy, from beginning to end.

When Francis left Rome’s Gemelli Hospital in 2023 after being treated for bronchitis, he ran into Serena Subania and Matteo Rugghia, a Roman couple who had just lost their five-year-old daughter to a debilitating genetic illness the night before. Subania pressed her head into the pope’s chest and wept, as he held her close and whispered words of consolation.

Yet for every such heat-warming scene, there were also murkier and more conflictual episodes.

In 2014 and 2015, Francis convened two high-profile Synods of Bishops devoted to the family, which culminated in a 2016 document titled Amoris Laetitia opening a cautious door to the reception of communion by Catholics who divorce and remarry outside the church. The outcome was praised as a long-overdue gesture of mercy by its supporters, but a vocal conservative contingent, including a number of cardinals and bishops, complained that the pope had stacked the deck in the synods and run roughshod over doctrinal and pastoral objections.

The same pattern played out in 2021, when Pope Francis issued a decree called Traditionis Custodes rolling back permission granted under his predecessor, Pope Benedict XVI, for wider celebration of the traditional Latin Mass. For a pope who extols tolerance, critics saw the move as needlessly intolerant; for a pope who celebrates diversity, it seemed to those critics an imposition of rigid uniformity.

At one point, conservative dissidents splashed posters around Rome mocking the pope’s own rhetoric, asking, “Frankie, where’s your mercy?”

There were moments when Pope Francis seemed almost the Mikhail Gorbachev of Roman Catholicism, a reformer whose willingness to buck tradition made him a sensation outside the Church and among marginal Catholics, but whose standing within his own flock, especially those most devoted and committed, could be uneven. An Italian poll in early 2023 noted the paradox that trust in the pope was almost 20 percentage points higher among Catholics who attend Mass only occasionally than those who go every Sunday.

Yet whatever a given observer may have made of Pope Francis, they nevertheless felt compelled to observe – indeed, so drama-filled was his reign that one could scarcely look away for fear of missing something important.

When Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Buenos Aires, Argentina, took over the papacy, the Catholic Church stood at an historical crossroads. With its social capital drained by centuries of secularization, and its moral standing badly compromised by decades of clerical sexual abuse scandals, the Church seemed adrift.

All that changed swiftly under Francis, whose maverick style and progressive agenda captured the imagination of the world and never let go. From migrant and refugee policy to climate change to the war in Ukraine, there wasn’t a major global debate in which Francis’s voice went unheard.

In a phrase, this was a pope who mattered.

Because Francis deliberately chose to elevate bishops around the would who broadly share his outlook, it seems likely the dynamics unleashed by his papacy will outlive the pope who set them into motion. Looking back at the life and legacy of this remarkable Chief Shepherd, therefore, is also, in a sense, to look forward at the Catholic future.

Italian roots and the Dirty War

Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s story begins in the northern Italian region of Piedmont in the 1920s, when the economic and political upheaval which would pave the way for the rise of fascism drove scores of Italians to emigrate. Argentina was a destination of choice, enjoying a higher per-capita standard of living in the early 20th century than virtually any country in Europe. Between 1860 and 1940, an estimated 1.4 million Italians settled in the country, and today some 60 percent of Argentines have at least some Italian ancestry.

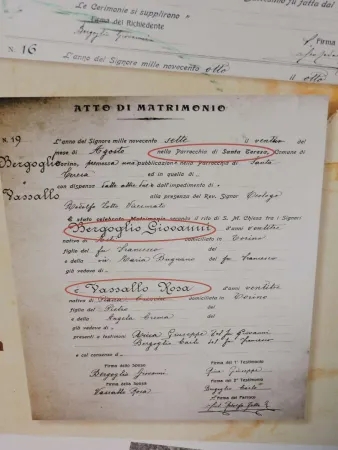

By 1927, two great-uncles of the future pope had already settled in Argentina, launching a successful paving company. Giovanni Angelo Bergoglio, the future pope’s grandfather, set sail from Turin to join them along with his wife, Rosa Margarita Vasallo di Bergoglio, and their six children.

The future pope’s father, Mario José Bergoglio, eventually found work as an accountant and married Regina María Sívori, born in Argentina to another family of immigrants from the Piedmont. The two settled in the Flores neighborhood of Buenos Aires, where their eldest child, Jorge Mario, was born on Dec. 17, 1936, and baptized on Christmas Day.

By his own account, a dominant influence on the young Jorge Mario was his grandmother, Rosa, who had been a leader in Catholic Action back in Italy and who became a pioneer in spreading Catholic social teaching in Argentina. Francis owed much to his grandmother’s imprint; he told the story, for example, of walking down the streets of Buenos Aires holding her hand when they spotted a couple of women from the Salvation Army. When the young Bergoglio asked if they were nuns, Rosa responded, “No, but they’re good people.”

Bergoglio felt the first stirrings of a vocation to the priesthood at the age of 12 or 13, but it was a slow burn. As a teenager, he swept floors, worked as a bouncer at a local bar and also served as an assistant at a food-testing lab. In that post, Bergoglio developed deep respect and affection for his female boss, who also happened to be an avowed communist.

After a romance with a neighborhood girl named Amalia and a health scare that led doctors to remove three cysts and a small portion of his upper right lung, Bergoglio decided to pursue the priesthood and became a Jesuit novice in 1958. He would spend two years in Chile studying, then three years of philosophy back in Argentina, three years of teaching high school, three more years studying theology, and a year in tertianship. He would be ordained to the priesthood in 1969, take his permanent vows as a Jesuit in 1970 and make the special fourth Jesuit vow of loyalty in 1973.

His formation occurred against the backdrop of the dramatic Second Vatican Council in Rome, which took place from 1962-65. Francis was the first pope since the council not to have participated in it directly, but it’s nonetheless fair to say that his entire life and priesthood was marked by the council and its aftermath; as pope, he would constantly cite Vatican II as the inspiration for his decisions.

Bergoglio became the provincial superior for the Jesuits in Argentina at the age of 36 in 1973, and a year later Argentina’s “Dirty War” broke out. Years later, a black legend would take shape accusing Bergoglio of complicity in human rights abuses carried out by the country’s military and security services, including the 1976 arrest and torture of two fellow Jesuits. In response to those claims, Italian journalist Nello Scavo published a 2013 book titled Bergoglio’s List styling him as a Argentine Oskar Schindler, documenting roughly a dozen people rescued by Bergoglio during the dictatorship and suggesting that for each person we know about, there were probably 20-30 more.

Bergoglio’s tenure as superior ended in 1979, and by 1980 he was sent into a quasi-exile. Rumors would suggest Bergoglio had been at odds with the liberation theology movement in Latin America, seeding a profile of him as a doctrinal and social conservative that would dissipate only after his election to the papacy.

The laboratory of Buenos Aires

Though Bergoglio may have been out of the public eye for most of the 1980s, he had become a friend and confidante of Cardinal Antonio Quarracino of Buenos Aires, and in 1992 Bergoglio was named an auxiliary bishop. He became well known in clerical circles for his work ethic and unpretentious style, moving around the city on his own via bus or subway.

While most bishops have a priest secretary to keep their schedule and act as a screener, Bergoglio made his own appointments by carrying around a small black notebook in his shirt pocket, a habit he continued even into the papacy.

While admirers see that independent streak as an expression of personal modesty, others detect something more cunning – a stubborn resistance to being “handled,” plus a preference for inscrutability that might be compromised by dependence on a gatekeeper who knew too much of the boss’s mind.

As Quarracino’s health declined, Bergoglio was named the coadjutor archbishop of Buenos Aires in June 1997, taking over the position eight months later when Quarracino died in February 1998. He would hold the post for the next 15 years, becoming a cardinal in 2001.

In some ways, that long run in Buenos Aires was the laboratory in which Bergoglio developed the theological vision and pastoral style he would later bring to the papacy. Looking back, there were four cornerstones of that approach:

- Closeness and service to the poor, such as the corps of “slum priests” he pioneered who live and minister in Buenos Aires’ notorious villas miserias, or “villas of misery.”

- A strong focus on popular faith and devotion, expressed in the great shrines and devotions of Latin American Catholicism.

- A missionary vision, getting the Church “out of the sacristy and into the street.”

- A rejection of clerical privilege, breaking the Latin American tradition of seeing clergy as part of society’s ruling elite.

Among other hallmarks of the Buenos Aires years, Bergoglio was the lead editor of the 2007 “Aparecida Document” of the Latin American bishops, the core idea of which was a call for a “continental mission,” going out to meet people where they lived.

In other ways, however, it’s impossible to draw a straight line between Bergoglio the cardinal and Francis the pope.

For instance, Cardinal Bergoglio was notoriously loathe to engage the media, granting only a handful of interviews over his 15-year term, while as pope it sometimes seemed he had joined the “interview a week” club; he disliked travel, preferring as much as possible to stay home, but as pope he took to the road with gusto; in Argentina he rarely emoted in public, earning a public reputation as a gray and stand-offish figure, while he would become the pope who turned the world on with his smile.

Despite all that, by 2005 Bergoglio was seen by his fellow cardinals as an able leader of one of the world’s largest and most complicated archdioceses, not to mention a figure who seemed equidistant from the liberal and conservative extremes of the Latin American church. That was enough for some cardinals, opposed to the idea of seeing the doctrinaire Joseph Ratzinger succeed Pope John Paul II, to look to Bergoglio as an alternative.

In the end, 2005 was not Bergoglio’s moment. Eight years later, however, his turn would come, though not in a fashion that virtually anyone might have expected.

A maverick from the beginning

Pope Francis turned out to be such a surprising figure that perhaps it’s only fitting his ascent was made possible by arguably the single greatest surprise in papal history in the last 500 years: The resignation of Pope Benedict XVI, which was announced on Feb. 11, 2013, and which took effect at 8:00 p.m. Rome time on Feb. 28.

For the next decade, the warm private relationship between Francis and Benedict would stand in contrast to their occasionally tense public co-existence, with Benedict emerging, against his own will, as a hero and inspiration to the new pope’s internal opposition.

Every conclave is, in a sense, a referendum on the papacy which has just ended. In 2005, cardinals believed they had just witnessed the close of an historically successful papacy under John Paul II, and voted for continuity by electing its intellectual architect in Ratzinger. Eight years later, however, the perception was different – after the explosion of the sexual abuse crisis and other scandals that plagued the Benedict papacy, including the disedifying “Vatileaks” affair, they were in the mood for a housecleaning, and thus turned to an outsider in the form of the 76-year-old cardinal of Buenos Aires.

Many of the cardinals who took part in that 2013 conclave would later confess they weren’t fully sure what they were getting when they elected Bergoglio. That was certainly true of the wider Catholic world. Many of Bergoglio’s fellow Jesuits, for instance, especially the more liberal variety, were initially despondent, fearing he would continue the crackdown on the order begun under John Paul II.

Such impressions, however, vanished as quickly as a morning dew in the summer sun, as the new pope quickly established himself as a strong break with the conservative governance that had dominated Catholicism for 35 years under John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

Right away, there were signals of a new order arising.

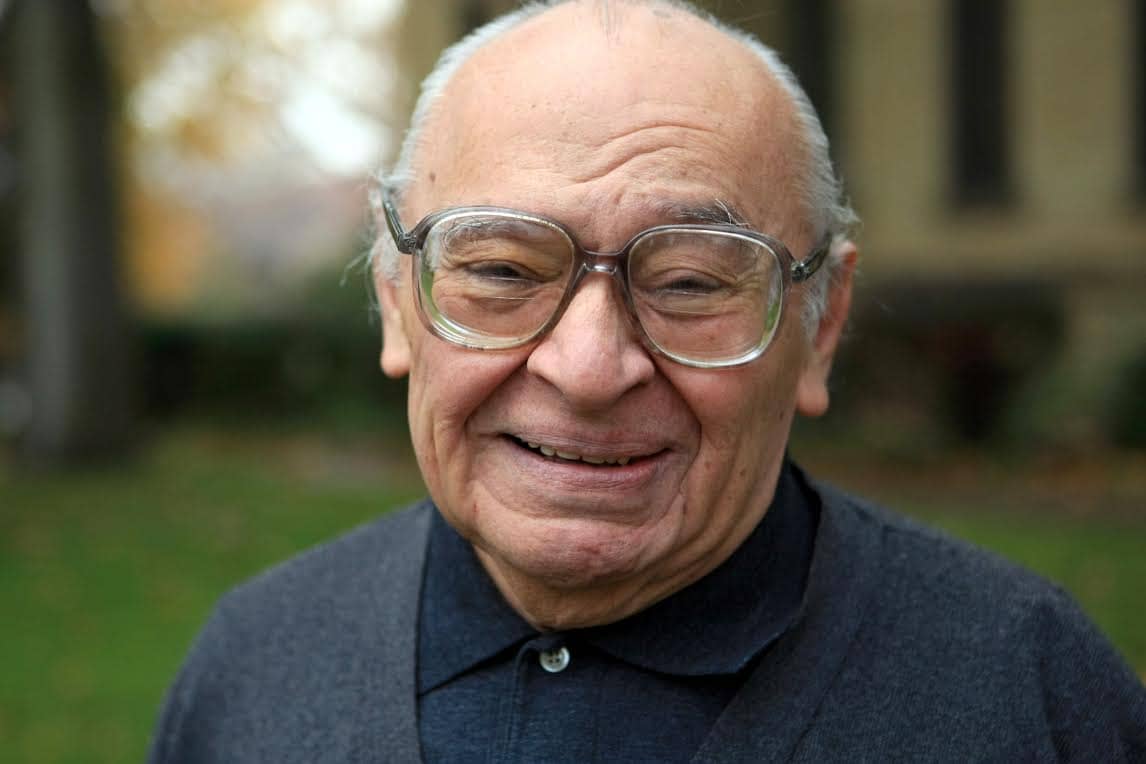

In his first Angelus address on Sunday, March 17, the new pope gave a shout-out to German Cardinal Walter Kasper, a figure who’d been marginalized under the old regime for what were seen as his dangerously progressive theological positions.

“In these days, I was able to read a book by a cardinal – Cardinal Kasper, a smart theologian, a good theologian – on mercy. It did me a lot of good, that book, but don’t think I’m just giving publicity to the books of my cardinals! It’s not like that! But it did me a lot of good, a lot of good … Cardinal Kasper says that to hear mercy, this word changes everything.”

It was an early hint that “mercy” would be one of the watchwords of the new papacy, as well as a foreshadowing of the controversial decision Francis would later make on the divorced and remarried, effectively adopting the position for which Kasper had long advocated.

Over the course of the next several weeks, Francis would continue to drop hints of things to come.

The new pope dispatched an email to Dominican Father Timothy Radcliffe, former Master General of the order, to express admiration for Radcliffe’s books and to indicate he was welcome in the Vatican. It marked a reversal of fortune for Radcliffe, whose progressive views on issues such as sexual ethics had left him on the outs during the John Paul and Benedict years.

A similar rehabilitation would later fall upon Cardinal Oscar Rodriguez Maradiaga of Honduras, whose career seemed stalled under Benedict but who was quickly named coordinator of the new pope’s Council of Cardinals, marking a comeback for liberation theology and the progressive social justice agenda of the Latin American Church.

Francis’s day trip to the Italian island of Lampedusa in June 2013, where he met with refugees in a detention center and laid a wreath in the sea to mourn the thousands who had died trying to cross the Mediterranean in search of a better life, was a downpayment on the progressive social agenda of the papacy.

The new pope’s unforgettable soundbite on a return flight from Brazil a few weeks later in response to a question about gay clergy, “Who am I to judge?”, likewise heralded a new preference for pastoral outreach and understanding over doctrinal clarity and the wars of culture.

In September 2013, Francis also made clear that the pope would no longer be the de facto chaplain of NATO, allying himself with Vladimir Putin of Russia in opposing Western military action to dislodge the regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria. Indeed, many diplomats would later credit the pope’s interventions with helping to prevent a wider conflict.

In most ways, the trajectory of the new papacy was set by the end of Francis’s first year in office – generating praise and acclaim in many quarters, but fear and ferment in others.

Sex and money

Francis was elected on a reform mandate, which above all meant coming to terms with two twin sources of heartache: The clerical sexual abuse crisis, which had rocked Catholicism to its core, and the Vatican’s own reputation for shady financial dealings, which had helped sour whole generations on Catholicism.

On both fronts, Francis often said all the right things, and he moved aggressively to achieve change – and yet, on both fronts, even the most charitable observers would be compelled to give him a grade of “incomplete.” More cynical voices would say be provided the theater of reform, but not the lived reality.

Early on, there was an attempt to discredit the new pope on the abuse scandals by pointing to a handful of cases he’d allegedly mishandled in his native Argentina. Upon examination, however, it emerged that Bergoglio either didn’t have jurisdiction over the clergy in question, or that the facts of the cases were still in dispute.

Meantime in Rome, Francis moved quickly to demonstrate seriousness of purpose, pledging a new spirit of transparency and accountability. He announced in December 2013 the creation of a new Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors to advise him on anti-abuse measures, to be led by Cardinal Sean O’Malley of Boston, perhaps the single prelate in the Church with the greatest credibility as a reformer vis-à-vis the abuse scandals.

Still, Francis remained a Latin American prelate who hadn’t experienced the scope and scale of the abuse crisis like his confreres in North America and Europe, and that lack of gut-level sensitivity occasionally broke through.

Initially, for example, he defended Chilean Bishop Juan Barros, who had been accused of being an accomplice of that country’s most notorious pedophile priest, Fernando Karadima. It took a disastrous trip to Chile in January 2018 for Francis to change course, eventually summoning all the Chilean bishops to Rome and receiving their resignations en masse.

Perhaps most damaging to Francis’s reputation were two specific cases: Argentine Bishop Gustavo Zanchetta, and Slovenian Father Mark Rupnik.

Zanchetta was an Argentine bishop, appointed by Francis to the small Diocese of Oran in 2013. In 2017 the pope brought Zanchetta to Rome and gave him a position in the Vatican’s financial administration, despite the fact he left Oran facing charges of both sexual and financial misconduct. In March 2022 Zanchetta was convicted by an Argentine court of aggravated and continued sexual abuse and sentenced to four and a half years in prison, which he’s presently serving under house arrest due to failing health. Although Francis in 2019 said that were also be a canonical process against Zanchetta, nothing is known about where it stands, and many observers believe there remain serious unanswered questions about the pope’s role in the case.

Even more disturbing has been the scandal surrounding Father Marko Rupnik, a celebrated Slovenian artist who’s been accused of various sexual crimes, including rape, against adult women over the course of almost 30 years. Rupnik was expelled from the pope’s own Jesuit order in 2023 after a prima facie finding of guilt, but was quickly incardinated into the Diocese of Koper in Slovenian with no objection from the pope. Making things worse, Francis later granted an audience to a longtime loyalist and apologist for Rupnik, and his own Diocese of Ro, he gave the Centro Aletti Rupnik founded in the city a clean bill of health while casting doubt on the charges against him. Francis later reversed course and ordered a canonical process to be opened, but as in the Zanchetta situation, as of now little is known about where that case stands.

Francis was a great legislator as pope, issuing more motu proprio (amendments to Church law on his own initiative) than any pope in recent memory, with many devoted to the abuse scandals. Perhaps most significant in this torrent of legislation was his 2019 decree Vos Estis Lux Mundi, creating for the first time a system for holding bishops and other superiors accountable not merely for the crime of sexual abuse, but also the cover-up.

Critics, however, insisted that the forward-looking nature of the pope’s legislation wasn’t always matched by aggressive implementation. Only a handful of bishops were subjected to Vos Estis investigations, for instance, and while a few quietly resigned in consequence, none were ever publicly sanctioned with the loss of their standing as a bishop or a priest, raising questions about the deterrent value of the policy.

Similar question marks surrounded the pope’s reform efforts on Vatican finances, where once again he promulgated new law with vigor, but the extent to which these laws were enforced to achieve real accountability is debated.

The centerpiece of that effort was undoubtedly a trial launched in the Vatican to great fanfare in 2021 against ten defendants charged with corruption in a $400 million London land deal, as well as various smaller-scale transactions. For the first time, the indictments also fell on a Prince of the Church, Italian Cardinal Angelo Becciu, who had served as the sostituto, effectively the papal chief of staff, under both Popes Benedict XVI and Francis.

While the trial was hailed as proof of the pope’s commitment to the rule of law, from the very beginning there were serious doubts about the integrity of the process.

For one thing, Francis issued a series of rescripts during the investigatory phase which, in the eyes of critics, stacked the deck in favor of the prosecution in ways inconsistent with accepted international standards of due process. For another, the presiding judge in the trial and the lead prosecutor were old rivals on the secular Roman legal scene, raising questions about whether the Vatican trial was actually an extension of their long-running hostilities by other means.

Most basically, many observers wondered how Becciu and the other defendants could be charged with crimes for transactions which were fully approved, in writing, by the highest authorities in the Vatican, including Venezuelan Archbishop Edgar Peña Parra, Becciu’s successor as sostituto; Italian Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Secretary of State; and, in at least some instances, by Pope Francis himself.

The nagging question that hung over the process from the beginning was whether the trial was an attempt to shift blame from Vatican superiors to lower-level figures, thereby transforming poor judgment and incompetence into a criminal plot. It also raised long-standing questions about the core integrity of the Vatican’s system of criminal law. Can any criminal justice process in which the chief executive, and thus the prosecuting party, is also the supreme judicial authority, truly be said to be fair?

In general, most observers give Francis enormous credit for good intentions on both the abuse and financial scandals, and agree that he’s created a tissue of new laws and policies that make a return to the status quo ante impossible. If the enforcement and application of those laws was at times uneven and unsuccessful, supporters would say those are the birth pangs of lasting reform.

Ad intra and Ad extra

Popes are called to lead both ad extra and ad intra, meaning in the wider world and inside the Catholic Church. On both fronts, Francis was a change agent.

Ad extra, the hallmarks of Francis’s agenda were the social gospel and multilateralism.

In terms of social teaching, Francis had four core priorities:

- Care of creation and the environment, the centerpiece of which was his 2015 document Laudato si’, the first papal encyclical ever dedicated entirely to ecological themes.

- Migrants and refugees. Memorably in February 2016, in response to a question about then-candidate Donald Trump’s proposal to build a wall along the US/Mexico border to keep migrants out, Francis said “this man is not Christian.”

- Interfaith dialogue, especially with Islam, including a “Document on Human Fraternity” jointly signed with Ahmed el-Tayeb, the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar in Cairo, effectively the leader of the Sunni Muslim world, as well as an historic 2021 encounter in Najaf, Iraq, with Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the most revered spiritual authority in Shi’a Islam.

- Conflict resolution, including playing a lead role in trying to bring peace to troubled settings from the Central African Republic to Ukraine and the Israeli-Hamas war in Gaza.

When it came to international affairs, Francis was history’s first truly multilateral pope. On the war in Ukraine, for example, Francis took a substantive position closer to that of Beijing, New Delhi and Brasilia than that of Washington, London or Brussels, expressing compassion for Ukrainian victims but refusing to condemn Russia outright and even suggesting that NATO may have been partly to blame.

Overall, the pope’s ambition was to inspire a 21st century version of the 1970s-era Helsinki process, which brought together all the nations of both the Soviet sphere and NATO to reduce tensions at the height of the Cold War.

Toward that end, he was willing to engage both Russia and China to a degree that often frustrated more hawkish elements of Catholic opinion. Their umbrage was especially aroused by a controversial 2018 deal with Beijing giving China’s Communist government a significant say in the appointment of Catholic bishops in the country.

One byproduct of Francis’s multilateralism was an occasionally strained relationship with America and Americans. Like many Latin American prelates, he came into office with an ambivalent attitude toward the United States, given its checkered history in the region. Throughout his papacy, some of the most vocal criticism of Francis came from American conservatives, both secular and Catholic. Yet he gave as good as he got – in 2017, two close friends and advisors published an explosive article accusing conservative American Catholics of forging an “ecumenism of hate” with Evangelicals, and at another point he accused EWTN, the conservative American Catholic media giant, of doing “the work of the devil.”

He was at it again on January 6, 2025 – perhaps not accidentally, the four-year anniversary of the Capitol Hill riots unleashed by frustrated supporters of then-defeated President Donald Trump. Now, four years later and his MAGA populist vision, including its decidedly anti-immigrant slant once more preparing to take office, Francis appointed the liberal Cardinal Robert McElroy of the border city of San Diego to Washington, setting up him to the U.S. church’s main interlocutor with the Trump administration. Holding a Ph.D. in American Catholic public theology, McElroy is pro-immigrant, pro-LGBTQ+, opposed to banning pro-choice Catholic politicians from communion, and a strong critic of spreading social inequality.

For all time, when asked what he made of Trump and Trumpism, Francis could point to McElroy and reply, “I rebut it thus.”

For those inclined to charity, perhaps it wasn’t so much that Francis disliked America, as the U.S. and its moods simply weren’t his top priority – in itself, perhaps, a wake-up call for some Americans accustomed to thinking of themselves as the center of everyone’s attention.

Another constituency that often felt aggrieved under Francis was Israel and Jewish leaders around the world, who accused the pontiff of false moral equivalence in condemning both the Oct. 7, 2023, unprovoked Hamas attacks on Israel, the most lethal assault on Jews since the Holocaust, and Israel’s resulting war of self-defense. Several Jewish leaders accused Francis of triggering a “crisis” in Jewish-Catholic relations.

Ad intra, the cornerstone of Francis’s agenda was the priority of mercy over judgment.

He was not really a doctrinal revolutionary; at key points, he fueled expectations of significant change in Church teaching on, say, birth control, or women’s ordination, or the blessing of same-sex unions, only to pull back.

What Francis did accomplish, however, was to create space in Catholicism for an open debate on those points. Theologians and activists who previously might have been investigated, disciplined, fired or even hounded out of the Church found they could make their arguments openly without fear of censure.

Perhaps even more consequentially, many ordinary Catholics whose lives didn’t quite adhere to the moral idea as presented in Church dogma felt more welcome under Francis. Products of broken homes, for instance, or gay and lesbian Catholics, or couple who made the choice to use birth control or to pursue IVF treatments, all may have felt better understood and encouraged by the pope of “Who am I to judge?”

Indeed, so strong was the emphasis on outreach to those at the margins that Pope Francis at times seemed to have a “Prodigal Son” problem. Those Catholics who followed the rules, who went to Mass and supported the Church, sometimes thought of themselves like the older son in the parable. They may have felt the pope was so busy embracing the outcasts that he neglected them, and could resent what they felt was his cavalier disregard of their efforts.

That was hardly the only ambivalence, even outright rejection, Francis generated over his turbulent term.

Opposition and blowback

To be clear, opposition to popes is an old story in Catholicism, stretching all the way back to the Biblical era. Paul’s letter to the Galatians recounts a first century showdown between himself and Peter, whom tradition acknowledges as the first pope, over the inclusion of the Gentiles which became known as the “Incident at Antioch.”

More recently, there’s been strong internal opposition to every pope since Vatican II. Conservative French Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre was so upset with progressive reforms under Pope Paul VI, now St. Paul VI, that he founded his own traditionalist seminary in Switzerland. Under John Paul II, now St. John Paul, a cadre of liberal prelates was unhappy enough that they founded their own informal club, dubbed the “Sankt Gallen Group,” to plot strategy for the next conclave.

Yet two factors made the backlash faced by Francis different.

The first is the simple fact that he stepped onto the stage in a moment when opinion about virtually everything is deeply polarized. A 2019 Carnegie Endowment for International Peace study found that mounting political polarization is a threat to democracy not just in the United States, but in a highly diverse set of nations including Bangladesh, Brazil, Colombia, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Poland and Turkey.

What’s true of the wider world, pari passu, is also true of the Catholic Church. It’s arguable that Francis exacerbated the polarization in Catholic life, but he certainly didn’t invent it.

The second and related factor is the rise of social and alternative media outlets, which often profit from and exacerbate extremist positions. As a result, the sheer volume of criticism any leader faces – “volume” both in the sense of amount, and also noise level – is qualitatively new.

In terms of Pope Francis, the crossing of the Rubicon arguably came with Amoris Laetitia in 2016. Prior to that moment, many Catholic conservatives still insisted that the alleged progressivism of the new pope was either largely a matter of style rather than substance, or a media invention based on a selective reading of his public comments.

After Amoris, however, that position became more difficult to sustain, and conservative opposition to the pontiff began to harden. One famous expression came with the dubia, meaning five critical questions about Amoris put to Pope Francis by a group of four well-known theological conservatives: Cardinals Walter Brandmüller and Joachim Meisner of Germany, Raymond L. Burke of the U.S. and Carlo Caffarra of Italy.

The fact that Francis never directly responded to the dubia, allowing the statements of other bishops and aides to stand as de facto replies, further rankled the pope’s critics, creating the impression of a pontiff indifferent to serious expressions of concern.

Certainly there were few modern precedents for the bombshell that went off in 2018, when a former Apostolic Nuncio to the United States, Italian Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, publicly charged Pope Francis with covering up sexual abuse and misconduct charges against Cardinal Theodore McCarrick (soon to be expelled from the priesthood) and called on the pontiff to resign.

While Viganò’s credibility as the pope’s accuser-in-chief dimmed considerably as his affiliation with various alt-right causes and conspiracy theories became steadily clearer, the battle lines he helped create nevertheless endured.

Conservative discontent with Francis simmered throughout his papacy, occasionally bursting into public view. In 2019, an open letter signed by more than 1,500 Catholic priests and academics accused Pope Francis of the “canonical delict,” meaning crime, of heresy.

During Holy Week 2023, a well-heeled campaign defending the Latin Mass splashed dozens of posters around the city of Rome, citing previous popes to effectively accuse Francis of betraying Catholic tradition.

Whenever he was asked about such backlash, Francis generally would project insouciance, saying only that it’s better when criticism is voiced to one’s face rather than behind the back. Critics, however, accused the pontiff of sometimes being vindictive with those who defied him, citing his preemptory firing in 2017 of three priests in the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith who allegedly had voiced traditionalist reservations about some aspects of the pope’s agenda.

However vicious the resistance in conservative and traditionalist quarters may have been, by the end of Francis’s papacy it seemed a legitimate question whether he had more to fear from his friends than his enemies. That was an especially compelling hypothesis watching the controversial “Synodal Path” play out in Germany, as a wide share of the country’s bishops and laity seemed blithely indifferent to papal warnings not to go too far, too fast.

While these fractures may not have slowed down Francis personally, they nevertheless represents a real pastoral challenge for whoever may succeed him, who will face the potentially thankless task of attempting to put Humpty-Dumpty back together again.

What Benedict stored, Francis scattered

One way to contextualize the Francis revolution is to see his papacy not in isolation, but as part of the broader reaction of Catholicism to the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), the watershed event to which Francis, in tandem with every pope since the council, continually appealed.

Viewed in that perspective, and cast at an extreme level of generalization, the roughly 60 years since the close of Vatican II can be divided into 30 years of basically left-leaning governance (John XXIII, Paul VI and Francis) and almost 35 years of conservatism (John Paul II and Benedict). Put differently, roughly half the post-conciliar period has been devoted to pushing the envelope on reform, and half to consolidation and ensuring that the doctrinal baby wasn’t tossed out with the bathwater.

What thus might strike some observers as the alternation of competing extremes – say, in the transition from Benedict XVI to Francis – can also, through the prism of providence, be seen as Catholicism’s instinctive genius for achieving balance over time.

In Catholic spirituality, it’s sometimes said that “what Benedict stored, Francis scattered.” The reference is to St. Benedict as the founder of Western monasticism, which saved Christian civilization at time of great social disintegration, and St. Francis as the founder of the mendicant orders, who produced a new springtime of evangelization in the Medieval world.

In his celebrated biography of St. Francis, the immortal G.K. Chesterton put it as follows.

“In the world of spiritual things, what had been stored into the barns like grain was scattered over the world as seed. The servants of God who had been a besieged garrison became a marching army; the ways of the world were filled as with thunder with the trampling of their feet, and far ahead of that ever swelling host went a man singing; as simply he had sung that morning in the winter woods, where he walked alone.”

In effect, Pope Francis was that man singing in our time, even if his tune wasn’t always music to everyone’s ears. This pontiff from “the ends of the earth” sent forth an army of “missionaries of mercy” from the besieged garrison that had been the Catholic Church prior to his election.

If his army encountered opposition, including from within, and if his campaigns met with only limited and mixed success, they nevertheless achieved a massive scattering of seed destined to continue to flower in unpredictable, and often disruptive, ways.

Pope Francis, to repeat, mattered. For any leader, it’s hard to imagine a better epitaph than that.