ROME – With more than 5,000 Catholic bishops in the world, it’s inevitable there will be a variety of personality types – some prelates are dedicated pastors, some are more akin to bureaucrats and middle managers, some resemble old-school politicians who never saw a baby they didn’t want to kiss or a back they didn’t want to slap, a handful are genuine intellectuals and cultural critics, and on and on.

In that menagerie, there are also always a few honest-to-God prophets, who constantly push the envelope, speak aloud what others are merely thinking, and never tire of challenging the status quo.

If a bishop is supposed to be the foundation of unity in his diocese, these prophet-prelates often are more akin to signs of contradiction, stirring consciences and arousing opposition in roughly equal measure, in the spirit of Matthew 10:34: “Do not think that I have come to bring peace upon the earth. I have come to bring not peace, but the sword.”

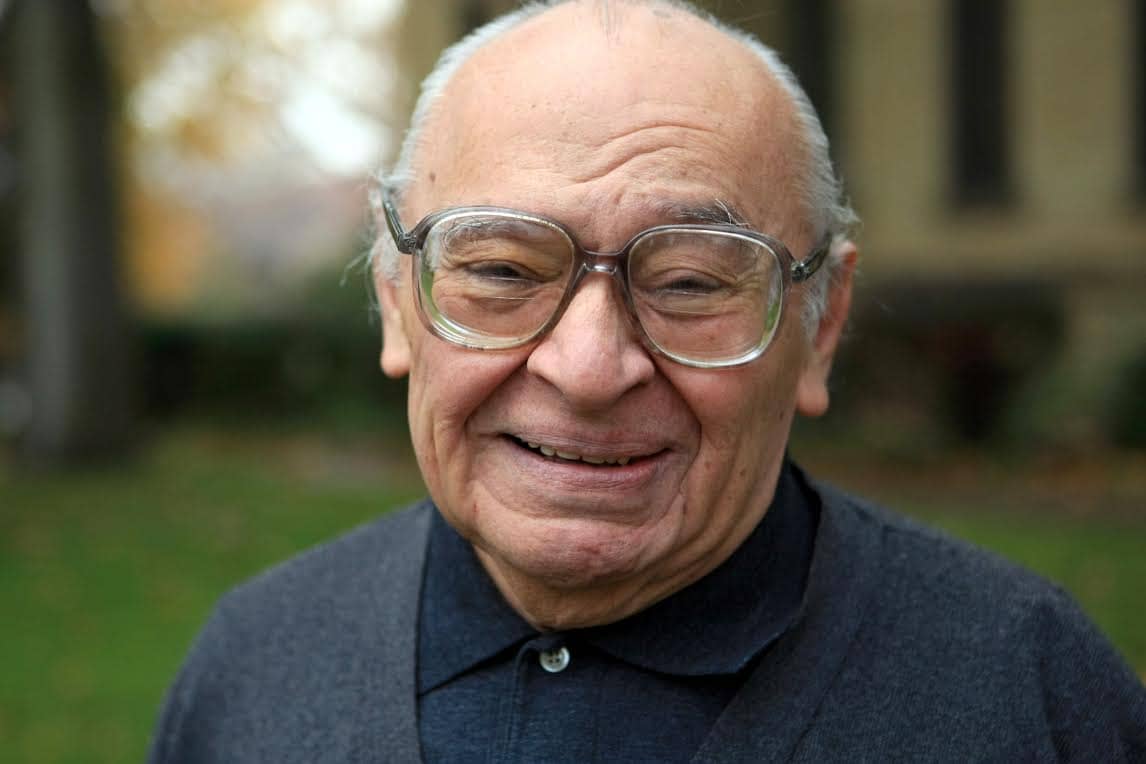

Such was the profile of Bishop Luigi Bettazzi of Ivrea in Italy, who helped to launch a movement in Catholicism which has reached a crescendo under Pope Francis, and who died Sunday just shy of 100 years of age.

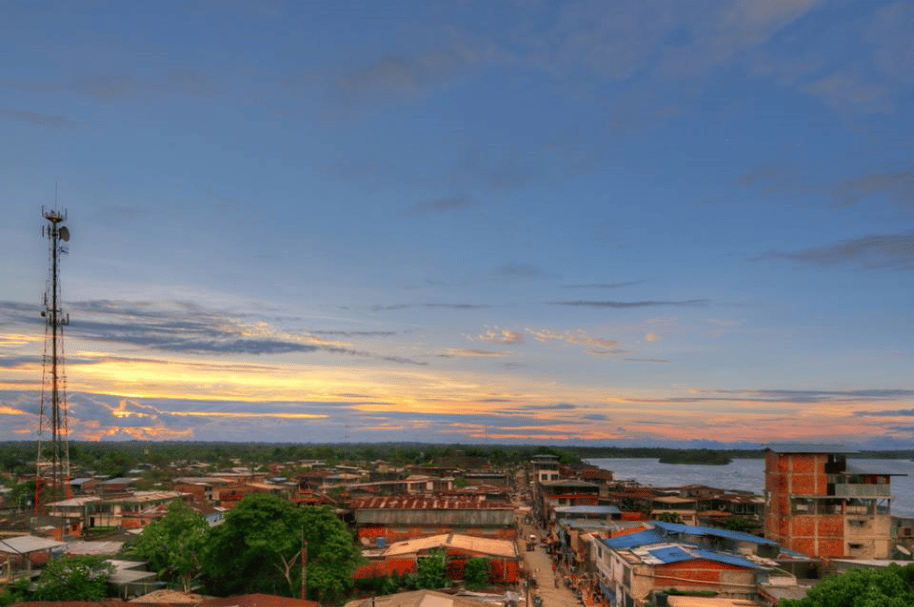

Bettazzi was the last surviving signatory to the “Pact of the Catacombs,” an agreement hatched towards the end of the Second Vatican Council by a group of 42 prelates to renounce wealth and privilege and to embrace a lifestyle of “evangelical poverty.” The group was led by Archbishop Hélder Câmara of Brazil, who would go on to become a major patron of Latin American liberation theology.

No prelate from the U.S. was among the original signatories, and only North American at all joined, Bishop Gerard-Marie Coderre of Saint-Jean-de-Québec. Later, more than 500 bishops worldwide added their names to the initiative. With Bettazzi’s death, there are only four Catholic prelates still alive who took part in Vatican II, the youngest of whom, Cardinal Francis Arinze of Nigeria, is now 90.

At the time, Bettazzi was a 41-year-old auxiliary bishop of Bologna, serving under the legendary Cardinal Giacomo Lercaro, who had proposed “the mystery of Christ in the poor” as a key idea towards the end of the Vatican II’s first session, and who would later carry the text of the Pact of the Catacombs to Pope Paul VI.

Among other things, the bishops pledged themselves to simplicity in housing, food, dress, to renounce titles of privilege such as “Your Excellency,” to support pastoral efforts among the poor and to assist in the development of the Church in poor nations.

To be honest, the pact was largely forgotten almost as soon as it was signed – Bettazzi would later say that Paul VI wanted to keep it quiet for fear that amid the tensions of the Cold War, it might come off as a political declaration in favor of the Soviets.

If keeping things quiet was the aim, however, Paul VI clearly had the wrong man in Bettazzi.

He would go on to protest the use of tax payments to fund military spending, to support a right to conscientious objection to mandatory military service at a time when doing so theoretically risked a jail sentence, and to support pacifist movements, including once helping to lead a peace march to Sarajevo during the 1990s Balkans War.

Most famously, in 1996 Bettazzi wrote an open letter to the then-secretary of the Italian Communist Party, Enrico Berlinguer. Technically speaking, a 1949 Vatican decree prescribing excommunication for espousing communism was still in force, and the reaction to Bettazzi’s opening was enormous.

“It’s for love of dialogue that I address you, and, in general, all those who’ve adhered to your party, above all their with their votes,” Bettazzi wrote. “I’m thinking of those who voted for you and are Christians, who don’t intend to renounce their religious faith and, perhaps while suffering for their disobedience to the hierarchy, nevertheless think they’re promoting a more just, more equitable, more participative, and therefore more Christian society.”

“Forgive me for this letter, which many will find naïve and not just a little at odds with my role as a bishop,” Bettazzi wrote.

“However, it seems to me legitimate and even a matter of duty for a bishop to be open to dialogue, committing himself in some way to realizing justice and growing a more authentic solidarity among people.”

The Italian communists were so stunned that it took them a full year to figure out how to respond. Berlinguer would eventually send a message that he wanted to meet Bettazzi, but the bishop was obliged to refuse the encounter on the instructions of the then-Patriarch of Venice, Cardinal Albino Luciani, who would later become Pope John Paul I.

Two years later, Bettazzi would join two other bishops in offering themselves as hostages to the leftist terrorist faction the Red Brigades, in exchange for former Italian Prime Minister Aldo Moro. The initiative failed and Moro eventually was executed, creating an open national wound that endures to this day.

To the very end, Bettazzi continued stirring the pot. In 2007 he came out in favor of civil unions for same-sex couples, and in a 2015 interview he condemned “neo-Platonists” who equate sex with sin, suggesting that even for homosexual couples, sexuality can also be an “expression of the human spirit.”

One has to imagine Bettazzi was gratified to see the first decade of the Francis papacy and his dream of a “poor Church for the poor.” In 2015, Bettazzi said simply that “the Pact of the Catacombs today … is Pope Francis.”

It will be up to history to judge to what extent Bettazzi anticipated movements that will become part of the Church’s common inheritance, and to what extent he perhaps went too far or occasionally put a foot wrong.

What’d undeniable, however, is that without Bettazzi, the Catholic Church will be just slightly less unpredictable, volatile and interesting, and for that, he certainly will be missed.