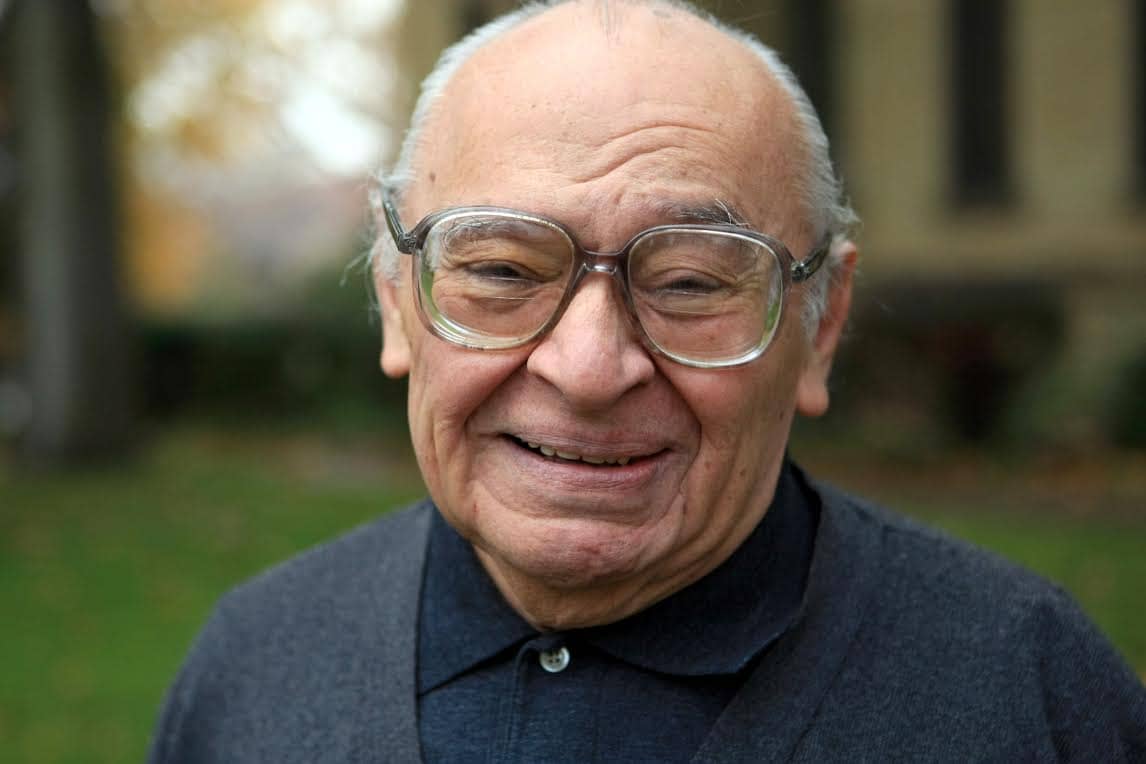

ROME – When Pope Francis returned to Italy yesterday after a brief overnight trip to Marseille, he found a country in mourning due to the death of former Italian President Giorgio Napolitano on Friday at the age of 98, after having been removed from life support at his family’s request three days earlier.

Napolitano was a beloved figure in Italy, remembered above all for his statesman-like role in the end of the regime of Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi in 2011 amid a massive debt crisis, engineering a transition to respected economist Mario Monti that many observers believe pulled the country back from the brink of economic collapse.

The irony that it was a former leader of Italy’s Communist party who effectively saved Italian capitalism was lost on no one.

It was actually Pope Francis who informally announced the end was near for the former president, speaking at the close of his General Audience on Wednesday.

“I urge you to spare a thought for President Napolitano, who is in grave conditions of health,” the pope said. “May he have comfort, this servant of the country.”

The fact the pontiff did not explicitly request prayers was, in a sense, a final gesture of respect, since Napolitano was a non-believer. His funeral, which is scheduled for Tuesday, will be the first for a former Italian head of state to be a civil ceremony rather than a Catholic funeral Mass, to be held in the chamber of Italy’s House of Deputies.

(I confess feeling a personal affinity with Napolitano, since he had an abdominal operation in 2022 at the same Roman hospital, Spallanzani, where I had my own esophageal surgery a few months later. We actually had the same surgeon, the supremely talented Giuseppe Maria Ettore. In a further connection, my wife and I were at Rome’s Salvator Mundi hospital last Wednesday for routine medical appointments, which was where Napolitano would die two days later.)

Often dubbed “King George” in the Italian press, Napolitano was the President of Italy from 2006 to 2015, making him the longest-serving president in the history of the Republic, and he was the first president ever reelected to the office.

From a Catholic point of view, there are two points of interest about Napolitano’s life and legacy, both with applicability well beyond the borders of Italy.

First, Napolitano’s career marked the definitive end of the old notion that the Vatican prefers to deal with Catholics in political roles, seeing the mere fact of being a practicing Catholic as a guarantee of personal virtue as well as sympathy to the Church’s positions.

In truth, by the time Napolitano first became Italy’s president in 2006, that concept already had outlived its usefulness. As far back as 1978, when Sandro Pertini was elected to the Italian presidency, Pope Paul VI made it clear that Pertini had his blessing despite being a socialist and self-declared atheist. Pertini was a strong anti-communist, a veteran anti-fascist, and never part of anti-clerical circles in Italian politics, qualities which counted more than his confessional affiliation.

Nevertheless, the dynamics of Napolitano’s reelection in 2013 were especially interesting, since one of the leading contenders at the time was former EU Commissioner and former Prime Minister Romano Prodi, a practicing Catholic especially close to progressive currents in the Church in his native Bologna.

Yet Prodi also was frequently at odds with leaders of the Italian Church, especially during the more conservative John Paul II and Benedict XVI years. Famously, he once referred to himself as an “adult Catholic,” thus not subservient to the hierarchy in his political choices, in the context of a 2005 referendum over liberalizing IVF, which Prodi backed and the powerful Italian bishops’ conference under Cardinal Camillo Ruini opposed. (Ironically, a much younger Ruini had celebrated Prodi’s wedding Mass in 1969.)

In that situation, it was widely understood in April 2013 that the powers that be at the Vatican and in the Italian church, largely holdovers from the Benedict XVI years, preferred the non-believing Napolitano to the Catholic Prodi, expecting (more or less correctly, as it turned out) that the Church/state relationship would be less contentious under Napolitano.

That’s a bit of history from which Americans in particular might be able to learn something.

Though it’s not quite an exact analogy with a head of state, consider the question of ambassadors to the Holy See. When it comes time to pick a new one, Americans still operate under the antiquated notion that the Vatican wants a Catholic. Wrong: What the Vatican really wants is a serious person with access and influence in the government he or she represents, and with a respectful approach to the church. Beyond that, whether the envoy is a practicing Catholic doesn’t really enter the equation.

Think about it: If the Vatican were to insist on dealing only with Catholics, where would that leave diplomatic relations with Israel? Or with Oman, where virtually all the Christians are non-citizen foreign workers and thus ineligible for diplomatic service? Or, for that matter, with Mongolia, where Pope Francis just visited and where there are fewer than 1,500 Catholics in the entire country?

Even in nations with large Catholic populations, in some ways it’s easier to deal with a non-Catholic, because then Rome doesn’t have to worry about his or her ecclesiastical standing. Recall that when the Vatican quietly turned down the nomination of Laurent Stefanini as France’s envoy in 2015, it wasn’t just because the former chief of protocol to then-President François Hollande was gay, but because he was a practicing Catholic whose views on same-sex marriage were at odds with church teaching.

In other words, the problem wasn’t that Stefanini isn’t Catholic — at least in part, the problem was precisely that he is Catholic. Opening the field to non-Catholics not only would avoid such headaches, but it also would have the advantage of significantly expanding the talent pool.

The second aspect of Napolitano’s story with clear Catholic relevance is his close friendship with Pope Benedict XVI, despite the fact that, politically speaking, the two men represented very different outlooks.

In July 2012, Napolitano authored a piece for L’Osservatore Romano, the Vatican newspaper, titled “My Friend Benedict XVI.”

“I don’t hesitate to confess that one of the most beautiful aspects that’s characterized my experience is precisely my relationship with Benedict XVI,” Napolitano wrote. “We’ve discovered together a great affinity, and we’ve lived a feeling of deep and reciprocal respect.”

The friendship between Napolitano, an ex-Communist and lifetime leftist, and Benedict, a hero to Catholicism’s conservative wing, irked many in both men’s political bases, but it was also a charming alternative to deepening polarization. Such was their bond that in February 2013, Napolitano was one of the few people to whom Benedict revealed his plan to resign the papacy in advance; Napolitano actually tried to talk him out of it, but Benedict insisted it was time to go.

Much was made of the juxtaposition of Benedict’s resignation in February 2013 and Napolitano’s reluctant reelection two months later, despite his expressed desire to step down. In both cases, many observers noted, the common term was a profound sense of responsibility which ran deeper than personal convenience.

Napolitano enjoyed a close relationship with Pope Francis too, but that’s more what one might expect given the similarities in their views. His friendship with Benedict, on the other hand, is, by the standards of our toxic times, a beguiling anomaly.

That lesson, too, is one which believers and non-believers alike, not to mention both liberals and conservatives of all stripes, might do well to ponder … and, just maybe, emulate.